Japan’s Middle Class in Crisis

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Japan was described as a “100 million middle-class society,” in which people who worked hard at corporate jobs and had a strong desire to consume supported economic growth.

But what is the current state of awareness of the middle class in Japan?

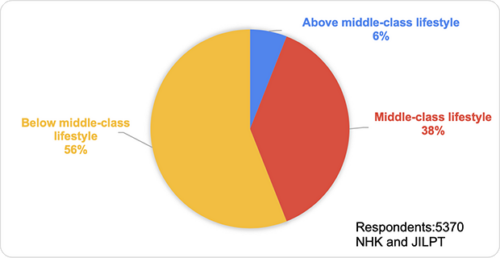

NHK, in collaboration with JILPT (The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training), conducted an online survey of men and women in their 20s to 60s across Japan from July to August this year, receiving responses from 5,370 people, and announced the results in September.

(Summary below)

When asked about the “middle-class life” they imagined, from multiple responses about 60% of the respondents chose “Full-time employee,” “Home ownership,” and “Private car” as indicative of a middle-class life.

On top of that, when asked if they were living the middle-class lifestyle they imagined, 56 percent said they were below a middle-class lifestyle.

It can be said that we are living in an era in which the life we imagine as middle class is not the norm.

Are you living the middle-class lifestyle?

Being a full-time employee is also considered a symbol of the middle-class—however, the income of full-time employees has fallen over the last 20 years.

According to JILPT, for both men and women, the lifetime wage of full-time college graduates is estimated to have decreased by more than 35 million yen compared to the peak period.

| Peak | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | 1993 | 287.8 million yen |

| 324.1 million yen | (-36 million yen) | |

| Women | 1997 | 240.3 million yen |

| 277.5 million yen | (-37.2 million yen) |

(JILPT)

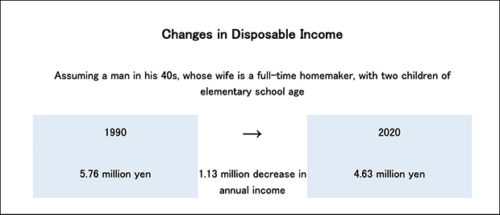

Disposable income was estimated by establishing a model family in Japan of the past: a man in his 40s, whose wife is a full-time home-maker, with two children of elementary school age.

The annual disposable income of this model household was found to have decreased from 5.76 million yen in 1990 to 4.63 million yen in 2020—a decrease of 1.13 million yen in annual income.

“Even if I continue to work as a full-time employee, I can’t live a comfortable life and I can’t escape my worries about the future.”

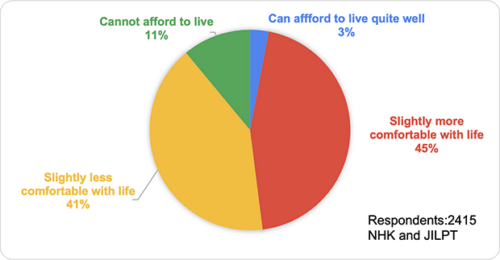

According to a survey conducted by NHK and JILPT, a certain percentage of people think this way.

When full-time employees were asked about their current lifestyles, 3% said they “Can afford to live quite well” and 45% said they were “Slightly more comfortable with life.”

On the other hand, 41% said they were “Slightly less comfortable with life” and 11% said they “Cannot afford to live,” which together accounted for more than half of all respondents.

Current livelihoods (full-time employees)

What should we understand about this situation, in which wages are not rising and working people do not feel “middle class”?

Professor Kohei Komamura of Keio University has this to say.

“After the bursting of the bubble economy and amidst growing globalization, Japanese companies found it difficult to stay profitable and increasingly tended to clamp down on labour costs without raising wages, and to save internal reserves.

If wages do not increase for working people, they will have no future prospects. This will lead to lower consumption and a declining birth rate, as well as growing concerns that society will become fragmented due to dissatisfaction and anxiety.”

He adds, “It is important to create a society where workers can plan their future with peace of mind. In order to achieve this goal, it is important for companies to consider not only short-term profits but also the position and situation of workers. On the other hand, workers also need to pay more attention to their own careers and skill development in order to design independent lives. The government needs to focus its policies on reviving the middle class by creating a system that guarantees security so that workers can have a better outlook on life.”

At the beginning of the extraordinary session of the Diet that opened on October 3, Prime Minister Kishida indicated in his policy speech the need for a “structural wage increase” as follows.

“Why have significant wage increases failed to be achieved in Japan over the years?

There is a structural problem. A virtuous cycle in which higher wages attract highly skilled personnel, which in turn increases the productivity of companies and generates further wage increases, is not functioning.

Once this cycle starts to move, investment in people will increase and this virtuous cycle will accelerate.

Therefore, we will promote an integrated reform of the three tasks of raising wages, facilitating labour mobility, and investing in people. Now that high prices are increasing and wage increases are an urgent issue, we will tackle this long-standing problem and aim to realize a structural wage increase.”

(excerpt)

After the bubble economy burst in the early 1990s, during what is known as “the lost 30 years,” workers’ incomes continued to fall after peaking in 1997 and the economy remained stagnant. Ultimately, wages in Japan have not risen, consumption has not increased, and economic growth has not been achieved. As a result, Japan is stuck in a vicious circle in which tax revenues also have barely increased for 30 years and the government is unable to formulate a credible growth strategy.

The number of births in Japan, which exceeded 2 million in 1973 during the second baby boom, lingered around 810,000 in 2021, a record low since the survey began in 1899. In Japan, as a result of the rapid decline in birthrates and the ageing of the population, the total population has started to decline from a peak of 128 million in 2010 to 124.8 million in 2021, a decline of more than 3 million people. The factors are complex, but one of the main reasons is that it is difficult for married couples to see a bright future.

There is no time to wait for government, labour, and management to realize a life in which working people can find hope for the future.